The Sorcerer’s Companion: A Guide to the Magical World of Harry Potter contains almost 100 illustrations, most of them historical. Here are a few of our favorites, along with excerpts from the chapters they appear in:

Owl

As far as we know, the wizards and witches of Harry Potter’s England are the first to be lucky enough to have reliable, door-to-door mail service provided by owls. However, the close association of owls with sorcerers does have a long history. Owls owned by the fabled wizards of medieval Europe are said to have been loyal companions, relied upon for their keen powers of observation and their ability to memorize complicated formulas and spells. According to legend, many an absent-minded wizard like Neville Longbottom sought the aid of a feathered friend when caught in a sticky situation.

Manticore

Now best known as the proud parent of Hagrid’s feisty blast-ended skrewts, the manticore was first described in the fifth century B.C. It was said to live in the jungles of India, where it enjoyed feasting on the local villagers. Although its reddish, hairy body resembled that of a lion, it reportedly had a human face, a melodious voice, and an extraordinary scorpion-like tail spiked with poisoned darts. The manticore could shoot these darts like arrows in any direction, striking its target at a distance of up to 100 feet.

Set in each of its enormous jaws and spanning the distance from ear to ear were three rows of razor-sharp teeth, perfect for reducing its prey into bite-size morsels. Good eater that it was, the manticore devoured its victims entirely, including skull, bones, clothing and possessions. When someone vanished from a jungle village without a trace, it was clear that a manticore was nearby.

Hinkypunk

Ron Weasley isn’t the only wayfarer to have found himself waist-deep in mud after an encounter with the wispy spirit known as a hinkypunk. In the folklore of England’s West Country, the hinkypunk is said to lurk in remote areas at night, waiting for an approaching traveler before he lights a lantern and steps into view. The weary pedestrian, overjoyed to see a flicker of light in the distance, heads toward it, mistaking it for his destination or for a fellow traveler up ahead on the trail. The next thing he knows, he falls in a ditch, sinks into a bog, or tumbles off a cliff—much to the amusement of the hinkypunk.

Potions

Potions, remarkable brews with remarkable ingredients, have always been an essential part of the magician’s toolkit. The witches of classical mythology cooked up potions to restore youth, turn men into animals, and make themselves invisible. Medieval legends and fairy tales tell of sleeping potions, love potions, potions of forgetfulness, and potions to cause jealousy and strife. Alice, in her journey through Wonderland, drinks one potion that makes her small and another that makes her tall. And it’s a potion that transforms Harry and Ron, at least outwardly, into two of their least favorite people: Crabbe and Goyle.

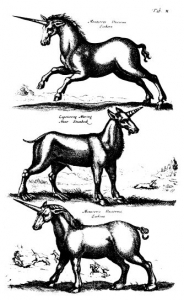

Unicorn

Few animals, real or imaginary, have captured the imagination as consistently as the unicorn. Ever since the single-horned creature was first described more than two thousand years ago by the Greek physician  Ctesias, people have written about, painted, sculpted, and hunted unicorns—all the while arguing about whether they really exist.

Ctesias, people have written about, painted, sculpted, and hunted unicorns—all the while arguing about whether they really exist.

The unicorns described in antiquity bear only slight resemblance to the noble, innocent, and pure creatures that inhabit the Forbidden Forest at Hogwarts. According to Ctesias, the unicorn was native to India. It was about the size of a donkey, and had a dark red head, a white body, and blue eyes. Its single, 18-inch horn was “purest white” at the base, black in the middle, and “flaming crimson” at the top. When made into a drinking cup, unicorn horn protected those who drank from it from convulsions, epilepsy, and poisons. Such vessels were not easy to come by, however, because the speed, strength and vicious temperament of the unicorn made the animal almost impossible to capture.

During the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, European travelers returned from Asia, Africa, and the Americas, with new reports of unicorn sightings. Since descriptions varied, unicorns were assumed to come in several types.

Broomstick

No one loves a broomstick quite like a witch. Harry’s great affection for his Firebolt makes it tempting to include wizards in this statement as well. Historically speaking, however, almost every person reported to soar through the sky on a broom was a woman. When the occasional wizard or warlock did lay claim to flying skills, his mode of transportation was most likely a pitchfork!

Between about 1450 and 1600, when belief in the power of witchcraft was widespread in Europe, witches were reported to take to the skies and head to their midnight gatherings astride not only broomsticks, but goats, oxen, sheep, dogs and wolves, as well as shovels and staffs.

According to popular lore, witches usually left their homes via the chimney, as in the illustration above. Once airborne, flying was said to be relatively easy—with two exceptions. A novice witch might have trouble staying on her broomstick, which was likely to be swift but unstable. Additionally, witches could be brought down—or prevented from taking off—by the sound of church bells. In the early seventeenth century a town in Germany was so fearful of bewitchment that for a time the city council ordered all churches to ring their bells continuously from dusk to dawn.

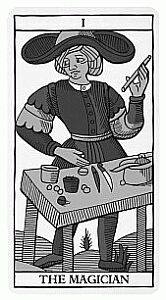

Magic Wand

Who among us hasn’t wished, at least once, for a magic wand? Simple, elegant, and easy to transport, magic wands are recognized around the world as symbols of the ability to make things happen. A wave of the  wand and poof—the dishes are done, your room is clean, your bowl of ice cream has tripled in size, and Aunt Henrietta just called to say she’s not coming after all.

wand and poof—the dishes are done, your room is clean, your bowl of ice cream has tripled in size, and Aunt Henrietta just called to say she’s not coming after all.

Before they graced the shops of Diagon Alley, magic wands appeared in cave paintings from 50,000 BC and in the art of the ancient Egyptians. The magicians of the Druid society presided over religious rituals with wands fashioned from hawthorn, yew, willow, and other trees they held sacred. By the early fifteenth-century wands were also a standard prop of the street entertainers who performed “magic” as a livelihood.

These tarot cards demonstrate two different ideas of the magic wand. On the left, the street magician’s wand serves as symbol of his profession and a useful device for directing the attention of his audience. On the right, an authentic wizard uses his wand to call down the powers of the heavens for use on earth.